Androgen Deficiency (late onset hypogonadism)

Overview

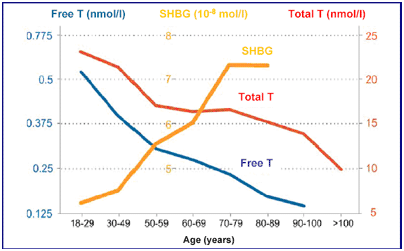

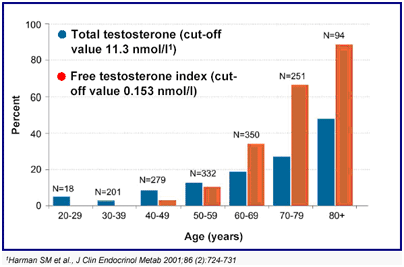

The male sex hormone (androgen) testosterone, produced by the testes under control of the pituitary master gland is essential for the maintenance of masculine characteristics and male sexual function. Testosterone production increases at the onset of puberty and reaches a peak in the late teens. While not as dramatic and sudden as the female menopause, for many years it has been accepted that circulating testosterone levels decline with increasing age. The terms male menopause, andropause, late onset hypogonadism (LOH), testosterone deficiency syndrome (TDS) and partial androgen decline in the aging male (PADAM) are all used to describe this decline in testosterone levels with advancing age. After the age of 50 years, levels fall by approximately 1% a year resulting in 20% of men over 60 having frankly low levels. However, due to the complexity by which testosterone interacts with other hormones which affect its biological activity, up to 70% of men over 60 years may have low levels of biologically active testosterone which are sufficient to cause them symptoms.

The symptoms associated with LOH can be divided into 3 main areas, those affecting sexual function, mood and cognition, and body characteristics (Table 1).

Table 1: Symptoms and signs associated with low testosterone levels

Sexual Function |

Mood/Cognition |

Physical Characteristics |

Diminished sexual desire (libido) |

Impaired intellectual and cognitive function |

Sleep disturbances |

Diminished erectile quality and frequency |

Low mood |

Decrease in lean body mass |

Diminished early morning erections |

Fatigue |

Reduction in muscle strength |

Hot flushes |

Irritability |

Increased abdominal fat deposition |

Diminished motivation |

Reduced body hair |

|

Diminished zest for life |

Decreased bone mineral density, causing osteopenia and osteoporosis |

While erectile dysfunction may be one of the most recognised symptoms, it is the decline in intellectual function and overall diminished zest for life which tend to be more common but usually elicited only on direct questioning. Due to the slow decline in testosterone levels, the onset of these symptoms tends to be insidious and otherwise attributed to ‘normal’ middle age. Not all of these symptoms need be present for the diagnosis of LOH and the severity of one or more does not necessarily match the severity of the others.

Diagnosis and Investigation

Confirmation of the diagnosis of LOH requires careful evaluation, preferably by an experienced endocrinologist. Diagnosis is based on a confirmatory history and symptoms, physical examination and laboratory investigations. A questionnaire is often used as a means of initial screening. As circulating testosterone levels are highest in the morning and fall during the day, blood measurements should be performed between 7 and 11 am, in order to assess the ‘best’ level. Other hormones should also be measured including the pituitary hormones, luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH), which influence testicular function, as well as sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) which influences testosterone’s bioactivity. Many other hormones also decline with age, including growth hormone and thyroid hormones, and these may also be measured. All of these assays are difficult to perform and therefore require a reputable laboratory. Variations between different laboratories means it is important to know the reference range of the laboratory used for the testosterone assay.

The vast majority of testosterone circulates in blood stuck to other substances, predominantly SHBG, with only approximately 0.5% being 'free' and biologically active. However, as measurement of free testosterone is difficult to do and the assays are unreliable, assessment of total testosterone is generally used as a surrogate measure together with levels of SHBG. Total testosterone blood levels below 8 nmol/l are generally accepted as being frankly low, and levels above 12 nmol/l as being generally normal. However, it is the grey area of levels between 8 and 12 nmol/l which account for the majority of men with LOH and in these men, a trial of testosterone therapy is often warranted for those with symptoms.

Treatment

There are a variety of different ways of administering testosterone including injections (either 2-4 weekly or larger depot injections every 2-3 months), oral tablets, or transdermal (skin) preparations (gel). The choice of which route of administration depends on individual preference but a gel if frequently used as the initial treatment as the increase in circulating testosterone levels is rapid and allows a quicker assessment of any improvement in symptoms. Administration is daily, preferably in the morning, to the skin of the upper arms, shoulder and/or abdomen as the gel is absorbed by the skin within a few minutes.

For patients with LOH, the benefits of testosterone therapy are usually rapid with marked improvement in many if not all the initial symptoms. In addition to improvement in sexual function, it is the restoration of overall intellectual function that many men find most gratifying combined with the return of their zest and motivation for life. Once improvement has been sustained patients often switch to longer acting depot injections which may be more convenient. The dose should be adjusted not only according to symptomatic response but also by regular blood tests to try and restore testosterone levels to those of a young adult.

Safety

Testosterone therapy is generally safe and very well tolerated with few significant side effects but careful monitoring by a specialist is mandatory. Stimulation of red cell production by the bone marrow will often increase the blood count and on occasions this will increase the viscosity of blood (haematocrit) to an unsafe level (increased risk of a stroke) and therefore require a dose reduction. Liver function blood tests will also require monitoring. The biggest concern relates to the perceived risk of prostate cancer. However, contrary to earlier reports, there is no evidence that testosterone therapy actually causes prostate cancer, and indeed rates of this cancer are actually increased in men with low testosterone levels. However, testosterone can worsen the disease in men who already have prostate cancer and for them it is contraindicated. Testosterone can also stimulate benign enlargement of the prostate gland and for this reason, regular monitoring of prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels should be performed.