Parathyroid

Primary Hyperparathyroidism

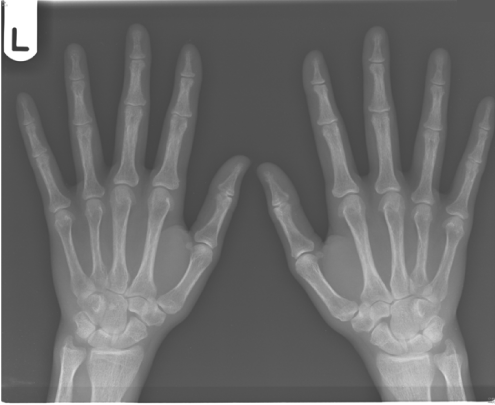

Primary hyperparathyroidism (pHPT) is the inappropriate excess production of parathyroid hormone. The term hyperparathyroidism was first coined in the 1920s to describe a syndrome characterised by bone disease, renal stones, fatigue, hypercalcaemia and high urine calcium. The diagnosis was dependent on symptoms related to “bones, stones, abdominal groans and moans” which often correlated with severe bone disease, advanced kidney disease, psychiatric and neuromuscular disorders respectively. The symptoms were often associated with evidence of calcification of the kidneys, bone erosion of the fingers, boney tumours and changes in the appearance of the skull on Xray.

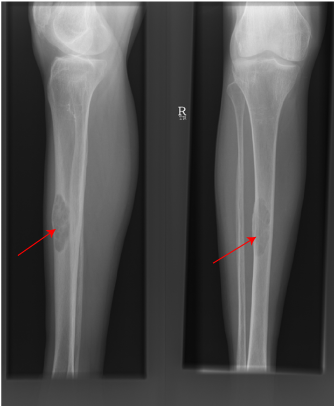

Brown Tumour of Tibia due to hyperparathyroidism

Over the years our understanding of calcium metabolism has improved and the disease has changed so that currently the definition of pHPT like the current commonest presentation of pHPT, is biochemical: hypercalcaemia (high blood calcium) in the presence of an absolute or relative inappropriately elevated PTH level. The disease now covers a spectrum that has extremes as diverse as asymptomatic normocalcaemic hyperparathyroidism to hypercalcaemic crises.

Primary hyperparathyroidism is the commonest cause of hypercalcaemia (high blood calcium) in the community. The prevalence of pHPT in Europe is now 3/1000, it is twice as common in females as males, and increases with advancing age in both sexes.

Subperiosteal bone erosion of proximal phalanges and metacarpals in hyperparathyroidism

Most patients with pHPT present sporadically with no apparent risk factors. The known risk factors for pHPT include radiation exposure, lithium use and a family history of hyperparathyroidism or multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes (MEN1 and MEN2A).

Clinical Features of pHPT

Whilst some patients may still present with renal calculi, bone disease and pancreatitis, pHPT the marked symptomatic form with severe skeletal and renal complications is today seen only in patients from developing countries. Elsewhere the disease is most commonly diagnosed in apparently asymptomatic patients.

“Asymptomatic” Primary Hyperparathyroidism

Whilst most patients currently diagnosed with pHPT are described as asymptomatic , the myriad of subtle clinical symptoms including malaise, fatigue, depression, memory loss, poor concentration, loss of libido, polydipsia, polyuria, constipation, non specific bone and joint aches are very common. Health related quality of life scores are reduced in apparently asymptomatic patients and they improve following parathyroidectomy. Furthermore asymptomatic pHPT is associated with higher rates of hypertension, dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance, unfavourable body fat distribution, cardiac and vascular dysfunction, and morbidity from cardiovascular diseases.

Symptomatic Primary Hyperparathyroidism

Amongst patients with symptomatic disease kidney stones are the commonest clinical feature. Renal stones and ureteric colic are significantly more frequent in younger patients where hypercalciuria (a high level of calcium in the urine) is commoner. However, kidneys stones may also be present with no symptoms, thus justifying ultrasonographic renal assessment in patients with proven pHPT.

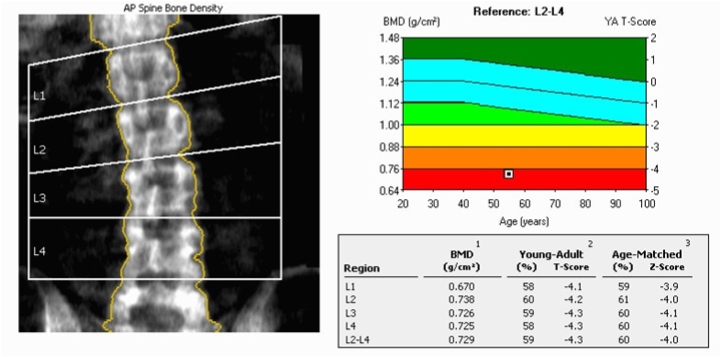

Bone disease (low bone density and osteoporosis) is common but less frequently associated with fractures than in the past. As bone disease may only present clinically and radiologically at an advanced stage, bone densitometry of cortical bone is required to demonstrate osteoporosis in patients with general aches in the context of pHPT.

Gastrointestinal symptoms resulting from smooth muscle relaxation include constipation, anorexia, nausea and vomiting. The high incidence of peptic ulcers and abdominal pain from other causes in patients with pHPT has been recognized for many years. Hypercalcaemia increases gastric acid secretion and may account for ulcer disease (which overall is now uncommon) and the ulcer-like pain in pHPT. Pancreatitis is been believed to be more common in pHPT and directly related to the hypercalcaemia of pHPT, but the mechanism by which this occurs remains unknown. The majority of patients with abdominal symptoms thought to be secondary to pHPT experience resolution their symptoms following parathyroid surgery.

DXA scan of Spine with severe osteoporosis

Hypercalcaemic Crisis

A hypercalcaemic crisis is an uncommon condition that occurs in no more than 1-2% of pHPT. It is characterised by a serum calcium that is very high indeed (greater than 3.5mmol/l) and is typically associated with a rapid deterioration in central nervous system, cardiac, gastrointestinal and renal function. The majority of cases are due to pHPT and are therefore also known as parathyrotoxic crises.

Parathyrotoxic crises tend to be subtle initially prior to developing overt confusion, delirium, abdominal pain (sometimes with pancreatitis), vomiting, dehydration and anuria, and occasionally with a palpable parathyroid adenoma in the neck. Life threatening arrhythmias may occur. Coma and cardiac arrest are possible in particular when serum calcium levels reach 3.75-4mmol/l.

The priority in hypercalcaemic crises is prevention rather than cure. This relies on avoiding dehydration by maintaining a fluid intake of 3 litres or more a day especially in patients with hypercalcaemia greater than 2.8mmol/L.

If prevention has failed or the serum calcium is >3mmol/l admission to hospital for in-patient management is adviseable since hypercalcaemic crisis in its acute form represents a medico-surgical emergency.

Urgent parathyroidectomy remains the most expedient method of restoring normocalcaemia and has minimal morbidity and mortality, with long term success rates similar to elective parathyroidectomy.

Normocalcaemic Hyperparathyroidism

Patients with normocalcaemic hyperparathyroidism are normocalcaemic but with a consistently inappropriately elevated PTH in the absence of secondary causes of hyperparathyroidism. The significance of this condition is controversial but once secondary causes of PTH elevation have been excluded there is a suggestion that it may represent the earliest form of pHPT, a phase characterised by elevated PTH that leads to a reduced cortical bone density but without hypercalcaemia. The second phase of pHPT is defined by the development of hypercalcaemia and therefore leads to the investigation and diagnosis.

The treatment of normocalcaemic pHPT remains controversial because the emergence of clinical features of pHPT is unpredictable as is the evolution to a hypercalcaemic state. The fact that some patients remain normocalcaemic despite the clinical manifestations of pHPT inevitably raises the question of the definition of a ‘normal’ serum calcium level for an individual patient. Each patient has to be assessed and treated on their specific merits.

Parathyroid surgery

Parathyroidectomy – surgery to remove a parathyroid gland - is currently the only available definitive cure for primary hyperparathyroidism. It is known to improve the bone, abdominal and urological effects associated with primary hyperparathyroidism. It frequently also improves the more subtle symptoms that often co-exist including fatigue, memory loss and reduced concentration. As a consequence surgery is usually recommended in all patients with primary hyperparathyroidism that have symptoms.

International guidelines recommend that a parathyroidectomy should also be considered in young (under 50 years) asymptomatic patients. Increasing evidence demonstrates that patients with long term untreated hypercalcaemia are susceptible to adverse consequences not only to the quality of their life but also they are more prone to heart disease as well as possibly malignancy. Parathyroidiectomy is associated with a quantifiable improvement in health related quality of life and may also normalise the long term risk of premature death especially in younger patients.

However, each patient requires assessment of their specific biochemical and clinical disease characteristics prior to contemplating surgery.

Minimally invasive parathyroidectomy

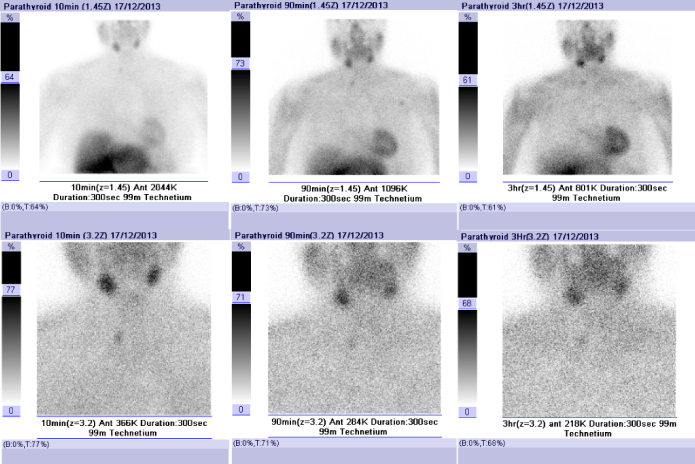

Traditional parathyroid surgery with a large scar, division of muscles and the use of drains should almost never performed today. Parathyroid surgery therefore is at least by traditional standards now always minimally invasive, including when all 4 parathyroid glands need to be identified. The principle of parathyroid surgery has always been the identification of all parathyroid glands (the normal gland is no larger than half a grain of rice) and the removal of the parathyroid tumour. Whilst this is the gold standard operation there is a co-gold standard minimally invasive operation that relies on the pre-operative scans. Indeed when pre-operative scans unequivocally locate the disease the option of targeted surgery (with intraoperative PTH if required) is a co-gold standard operation with equivalent results. Reliable preoperative localisation studies including sestamibi scanning, high resolution ultrasound and 4D CT scanning permits the identification of the diseased parathyroid gland in the majority of cases, so most patients are candidates for a minimally invasive parathyroidectomy.

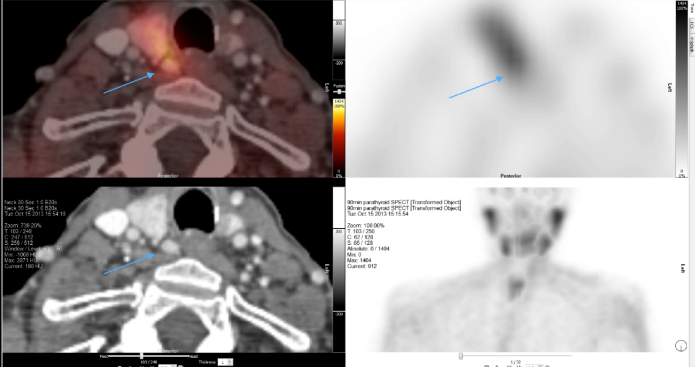

Sestamibi scan showing right sided parathyroid adenoma

Many techniques of this minimal access parathyroidectomy exist including endoscopic parathyroidectomy, video-assisted parathyroidectomy, and mini incision parathyroidectomy under general or local anaesthesia. The principal advantage of the minimally invasive parathyroidectomy is that when performed appropriately it allows the parathyroid adenoma to be dissected and removed through a small incision, leaving the other neck tissues undisturbed. In the hands of specialist surgeons this technique offers results equivalent to the best traditional operation but with the added advantages of (i) a smaller incision, (ii) a shorter operation, (iii) shorter hospital stay and (iv) the possibility of a local rather than general anaesthetic. Intra-operatively it is now possible to measure the patient’s PTH level in addition when necessary to assess the parathyroid gland with the use of a microscope.

The variation in the position and appearance of diseased parathyroid glands means that irrespective of the technique used, the experience of the surgeon plays a major role in determining the outcome of this surgery.

First safe with minimal risks of complications. Despite the various aids currently available to increase the success rate of surgery the single largest determinant of outcome following parathyroid surgery is the experience and current practice volume of the surgeon undertaking the procedure. Failure to cure at the first operation commits the patient to re-operative parathyroid surgery.

Re-operative Parathyroid Surgery

This is the surgery required when the patient has not been cured by the first operation elsewhere – a special interest of our service. Inevitably this is more challenging surgery since the disease gland is elusive with the added problem of the scarring from the previous surgery. Care in such cases requires a careful evaluation of the previous surgery, scans and histology.

4D CT localising parathyroid in re-operative surgery

Kidney stones